New York is a city of few ruins. "Disuse" is not part of its architectural lexicon; it has too little time and too much money to linger over its false starts and lighting-quick changes of direction. Wander through the city, and you might stumble upon a rubble-strewn block, a dilapidated pier, or a stubbornly incongruous armory, but these neglected corners are only temporary, they are the ungainly exceptions. Given a year, a week perhaps, they will be scrubbed clean, renovated, commercialized, reused, redeveloped. Amnesia is Americas' disorder of choice, and New York has been working to give this affliction its own anxious spin. Like a hardened lover, the city can bury its dead and move on with a determination that is as reliable for its completeness as it is terrifying for its speed.

But ruins are what brought me to Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens during the summer of 2002. Ruins, of a sort. The park, the borough's largest, includes a large art museum, a massive spread of well-kept foliage, a collection of closely packed stadia, and, near the park's periphery, the concrete skeletons of New York's 1964/65 World's Fair. I did not have to search the park for the Fair's ruins: their profiles incise the skyline, and can be easily seen from half a mile away.

I was not there only to see the fair grounds. I would first visit the park's Queens Museum (also a relic from a World's Fair, but in this case that of 1939), to see a work by the Palestinian artist Emily Jacir memorializing ruins of a very different kind, ruins over half a century old, and involving the dispossession of 4 million refugees. Her work's title explains quite a bit: Memorial to 418 Palestinian Villages which were Destroyed, Depopulated and Occupied by Israel in 1948. But what the title does not explain is that this park contains a key chapter of the collective biography of the Palestinians – a biography still unfinished, and from its beginning steeped in tragedy.

_____________________________

Although issued in dislocated installments, unfinished vignettes, and dangling plot lines, Jacir’s project does have a concrete beginning: Israel’s 1948 war for statehood, a war that resulted in the expulsion of 780,000 Palestinians. The thousands who were driven from their homes and dispersed across six continents became the first generation of a group of refugees whose numbers have grown to well over 4 million. Aside from unfailing admirers of American imperium, it’s generally understood that the “right to return” is a necessary part of any peace negotiation. It is also, predictably, the most despised, threatening, and eagerly discarded subject for American and Israeli politicians across the spectrum.</p>

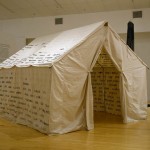

Against this fading of memory, Jacir began her memorial project in the spring of 2001, during her residency in P.S.1's National Studio Program. For the studio program's May exhibition, curated by Paulo Herkenhoff, she proposed installing a refugee tent embroidered with the names of the 418 villages that had been depopulated and destroyed during the 1948 war and afterwards. She began working in earnest, thinking that it would be feasible to sew all of the names into the tent by herself in a few sleepless weeks. It quickly became apparent that she could not even make a dent in the work. After receiving an email from Jacir asking for help with the project, friends and strangers began arriving at her studio in downtown Manhattan at all hours of day and night in order to lend a hand. Eventually the piece took on a new, more social dimension. On some nights, over a dozen people would participate in order to sew the letters. A few of those who showed up wanted to find the villages where their families came from; several people learned of the expulsion for the first time. Palestinians, Israelis, Americans, Egyptians, Syrians, Yemenis, Spaniards, and others sewed, told stories, joked, and gossiped.

The guiding resource for the work was Walid Khalidi's All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Cinderblock sized and maddeningly detailed, Khalidi's study documents the former sites of the 418 villages. Those who visited the studio spent as much time reading through the text as they did sewing. For participants who did not speak Arabic, names were slowly sounded out, matched with those on the quilt, and memorized, sometimes successfully, often not. Where is this town exactly? Have you been there? Did you say that that woman who was here yesterday had family there? Where did they all go?

After many weeks, and with the participation of several dozen people, the piece was installed, unfinished, in the main space of P.S.1's Clocktower gallery. Jacir also exhibited a day-by-day roster of sewing participants, along with texts written by many of them about their experiences in the studio. Khalidi's book was not displayed, but was present in much of the conversation surrounding the work. Through Jacir's tent, the book became not a record of a dead history, but a living thesis.

_____________________________

What remains has been a long-standing preoccupation for Jacir. In retrospect, the theme seems to have been in gestation, becoming more defined with each consecutive work. But in 1998, when Jacir produced her project Change/Exchange as a resident at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, she had no idea it presented a thematic departure point for much of what followed. It is a simple piece, made with exactly one hundred American dollars and about sixty currency exchange offices. The system is also rudimentary: exchange the American dollars for French Francs, keep a receipt, snap a picture of the office, note that a small sum was lost in the transaction, find another exchange and convert the Francs back into dollars, again snap a photo, keep the receipt, note the loss. Repeat until broke.</p>

Considered in isolation, Change/Exchange seems to be a trim exercise in neo-conceptualism, and if it were not for the later, more vigorously political pieces, one could see it simply as an absurd system of diminishing returns, a flagrant wasting of what probably were, for the artist, sorely needed funds. But keeping the later works in mind, one sees here the themes that would later become only more personal and urgent. No matter how modest the scale, or how subdued the subject matter, it is easy to see in the work's frantic migration, its crisscrossing of borders, the plight of Palestine. And isn't something here lost as well, albeit not as precious as land or human lives, but perhaps, as in the case of Palestine, as frustratingly irreclaimable?

Two years later, Jacir completed a series of drawings titled From Paris to Riyadh (Drawings for my mother). They are a collection of white vellum pages spotted with floating black ink forms, which, at fist glance, resemble patterns for the clothing of paper dolls. After a moment of inspection, one quickly realizes that the isolated arms, legs, torsos, and profiles correspond to the exposed skin of the models in an issue of a fashion magazine. The body parts are female, ridiculously thin, and coolly posed. But the reason for this soft censorship remains obscure until one considers the artist's biography, or rather that of her mother. While traveling by plane to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where the Jacir family lived while the artist was young, Jacir's mother would have to draw with marker over all the exposed skin in her fashion magazines, lest airport censors confiscate the material. Like all fig leafs, the black forms comically call attention to what should be hidden, and force one to imagine what is supposedly so hazardous to see.

Crucially placed covers became the literal and metaphoric basis for an untitled installation Jacir produced with the artist Anton Sinkewich in 2001. The work was made with books about or by Palestinians, which were wedged into the space between two gallery walls, forming a tightly packed, floating row. The volumes were rendered unreadable: the tension of the row would be broken if one book were pulled from the collection, sending the entire piece tumbling to the floor. If the compressed bibliography could not be read, it was at least allowed a presence within the gallery, but this presence, although tense, was so slight that one could easy miss the work. Even if noticed, a museum visitor could jot down a title or two for later reading, but would learn next to nothing about the volumes' contents. As with the names on Jacir's refugee tent, the untitled installation laconically issues signs requiring elaboration, but does not attempt a further explanation. Like the tent, the installation of books even betrays a pessimism about the very possibility of this elaboration.

While Jacir was in Marfa, Texas in October 2002, she could drive where she pleased without being stopped – an experience very different from that of all Palestinians living in Palestine, who face a repressive network of Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks. After filming the countryside for one hour during a drive through the barren Texan landscape, she asked Palestinians to suggest what songs they would play in their cars if there was "no Israeli military occupation, no Israeli soldiers, no Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks, no 'bypass' roads" in Palestine. The fifty-one songs on the play list were varied and often amusing, including Arab and American pop songs as well as Arab nationalistic anthems. The resulting work, from Texas with love, displayed the video of her trip with a soundtrack of all of the requested songs.

Whether through dissolution, repression, concealment, or suggestion, each of these four works is created around absences; they each draw attention to a lack, never fully make up for it, but rather simply point to it. In Change/Exchange the loss is economic, and is facilitated by the crossing of international borders. From Paris to Riyadh (Drawings for my mother) erases sexuality by paradoxically filling it in, becoming a ghoulish assemblage of fragmented body parts. Jacir and Sinkewich's untitled installation of books gestures to a body of literature, while rendering its contents inaccessible. And although a Palestinian might enjoy the imaginary moment of being able to drive through Palestine free of the constraints of an occupation, from Texas with love also carries with it the reality that this is not the case, and what one watches is in fact an American state, not a Palestinian one. The freedom that the work invites Palestinians to participate in is only a momentary fantasy.

_____________________________

An unusually cold summer drizzle was falling as I walked across the park toward what is perhaps the most out of place historical monument in New York City. On my way to the Queens Museum, I was looking for a 1,800-year-old pillar from the city of Jerash, a gift from King Hussein of Jordan to the City of New York, which has become well hidden among the manicured trees and flowerbeds of Flushing Meadows.</p>

This ruin too would play a part in Jacir's installation at the Museum. Only five minutes away, Jacir had installed her refugee tent as part of the museum's Queens International – an exhibition showcasing artists then residing in the borough. With over 130 languages spoken and close to half of its population foreign born, by many estimates Queens County is the most diverse county in the nation, and one of the most diverse areas in the world. The museum's organizers correctly understood that an exhibition made up of artists living in the borough would be international in scope; the 40 included artists were from 12 countries, and it would be safe to wager that a fair number of them, as of this writing, have since moved from Queens. (Jacir, for one, left the borough less than a year later.)

When invited to participate in the show, "the tent," as it became known, remained unfinished, appropriately perhaps, and had been shown almost without rest since its first exhibition at P.S.1. By that time, Jacir felt as if the constant unpacking of the work had become more than slightly burdensome – it was time to produce something new. But the pillar of Jerash, the park's remaining fair grounds, and the history of the museum itself would make her decide otherwise.

A few months before the show, during a walk through the Queens Museum's permanent exhibition on the 1939 and 1964/65 World's Fairs, Jacir learned that the museum had served temporarily during the 1940s as the home of the United Nations. Her surprise was as immediate as her decision to show the work for the museum's upcoming exhibition: surely, there could be no more apt location for the refugee tent. It was there, on November 29, 1947, that the General Assembly's Resolution 181 to partition Palestine was made. After a few weeks of research at the permanent UN headquarters, Jacir selected photographs taken after and before the partition meetings and had reproductions made.

But the weave of historical coincidences began to tighten when Jacir spoke to her mother about her time as a docent in the Jordanian Pavilion during the 1964/65 World's Fair. It was the Jordanian pavilion that had placed the pillar of Jerash in the park. The pillar is the sole architectural remnant of King Hussein's ostentatious national advertisement. A further detail of the pavilion would find its way into Jacir's installation, and ultimately would almost overwhelm it: the pavilion contained a mural and poem eulogizing the Palestinian refugees of 1948, which, predictably, caused an immediate controversy. The mural and poem were on view at the pavilion, but were also distributed by docents in pamphlet form. The poem begins:

Before you go,

Have you a minute more to spare,

To hear the word on Palestine

And perhaps to help us right a wrong?</blockquote>

Israel is not mentioned by name in the poem, but its settlers are evoked:...Strangers [came] from abroad,

Professing one thing, but underneath, another,

Began buying up land and stirring up the people.Neighbors became enemies

And fought against each other,

The strangers, once thought terror's victims,

Became terror's fierce practitioners.</blockquote>

The American-Israeli pavilion was not pleased. Nor were Jewish groups, nor the whole of the city government – protests were planned and carried out, arrests were made, and at least one official from the fair resigned. Someone replaced the Jordanian flag over the pavilion with an Israeli one. A parody of the poem was installed in the American-Israeli pavilion. This was front-page news in 1964; the New York Times carried the story regularly for several months. Robert Moses, the Commissioner of Parks, the Fair's organizer, and easily the most powerful man in the city, was apoplectic.Moses intervened immediately after the first protests, telling the Jewish groups and the whole of New York's government that the mural would stay put. They should also, he added, take their placards elsewhere. According to Moses, the fair was not a place for political demonstrations, and in the interest of the fair's "Peace Through Understanding" motto, all concerned should let the matter drop. Moses reserved the same attitude for other protests that took place in the park, including those around the issue of civil rights in the United States. He also menaced Arab protestors with arrest when they threatened to stage a counter-protest outside the American-Israeli pavilion. It should be obvious that Moses' actions were not in the interest of free speech; rather, he did not want a political challenge from any quarter.

A smaller but only slightly less vociferous reenactment of the 1964 debate was about to take place. Jacir installed the refugee tent within the center of one of the more prominent galleries in the museum, and to one side of the tent, three vitrines displayed reproductions of the photos taken during the partition meetings. A single photo was hung on a wall nearby, showing three delegates (from Pakistan, Uruguay, and the Jewish Agency) scrutinizing the Palestine exhibit at the U.N. on April 16,1948. On a nearby wall Jacir made available a perfect reproduction of the original pamphlet from the Jordanian pavilion, complete with the mural and poem. Flanking the pamphlets was a short statement on the historical documents and a reproduction of an email Jacir received from the original mural's painter, Muhanna Durra, who at the time of the Queens International was living in Cairo.

Within a few weeks of the show's opening, the Museum's director, Tom Finkelpearl, began to receive phone calls ranging from the inquisitive to the irate. What is this pamphlet my child brought home from the museum today? Why is the museum supporting anti-Israeli propaganda? After a number of calls, Finkelpearl, decided to withdraw the pamphlet from the installation until something could be worked out. It was becoming apparent that Jacir's distribution of the pamphlet was becoming confused with the museum's endorsement of it. Soon thereafter, a headline from the reliably right-wing Jewish Press read: "Propaganda or Art? Queens Museum Withdraws Arab Pamphlet 'For Now.'"

Finkelpearl determined that the pamphlet should stay on view, but not be passed out to the public; it would remain available on request. On each brochure Jacir was to affix a small label reading: "I reprinted this brochure from the 1964 World's Fair as my artwork – Emily Jacir." Jacir could only distribute the pamphlet either through the mail (without the sticker) or in person at the gallery during the opening – an impractical solution that effectively halted its dissemination. The pamphlet was transformed into a historical relic, instead of a work to be actively distributed. All sides were placated, but none was entirely satisfied.

Jacir arranged a panel at the museum on Resolution 181 and its aftermath. The panelists, Palestinian and Israeli, spoke not about how their lives were changed by the 1948 war – they were too young for that – but how that date placed them where they are today, how it gave them a homeland, or sent their families down a long road of dispossession. At first the discussion seemed incongruous, far from Israel-Palestine, in a comfortable borough of New York. But the building was, not long ago, a seat of world power. Now it is on the margins among the anomalous ruins of an amnesiac city. These panelists also had something to find in those ruins. And they too had an amnesia to struggle against.

Yes, New York is a city of few ruins. Those surviving pavilions in Queens are part of a small history, all glitter and glazed-eyed wonderment. No one believes that the fair grounds hold any power over the future anymore, and soon they too will probably disappear. But the ruins of Israel-Palestine – those of 1948, 1967, those of today – if distant from this park in Queens, are not entirely disengaged from its history. No matter how improbable it might be, these two sites share the same ghosts. It was here the ghosts were made, and through the work of Emily Jacir, it is here they have returned.