John Menick | Art | Writing | About | Newsletter | Instagram

Telharmonium

2025, generative film and score, custom software, 4K video, stereo sound

Score by Ben Shirken

Commissioned by MATTA

Telharmonium is a generative film exploring the automation of culture through one of the earliest electronic instruments: the Telharmonium. As in much of Menick’s work, the film links the history of technology with contemporary anxieties about artificial intelligence and the mechanization of creative labor.

The Telharmonium is often regarded as the first synthesizer. Built in the 1900s by American inventor Thaddeus Cahill, the instrument consisted of keyboards powered by enormous electrical generators. The device weighed over two hundred tons and filled a New York basement. For the first time, a single electrical current could imitate the sounds of multiple instruments, including the violin, flute, and piano. Remarkably, the Telharmonium’s music was transmitted over the still-new telephone network. For a fee, restaurants, hotels, and private subscribers could listen to performances played blocks away in the “Telharmonic Hall.”

Like the player piano and phonograph, the Telharmonium was an early attempt to automate cultural labor. By centralizing musical creation, the work of a team of keyboardists could replace the live orchestras that once entertained fashionable restaurants. Later instruments, including the Moog synthesizer and the drum machine, carried the same promise: one performer could stand in for an ensemble, or a machine could dispense with musicians altogether. For Menick, these tensions echo today’s debates over AI and creative work. Just as the Telharmonium foreshadowed the replacement of live musicians, AI now imitates artistic styles with startling accuracy, raising fears that cultural production itself may be overtaken by Silicon Valley.

As with its subject, Menick’s film is conceived as a complex machine, algorithmically changing in real time. At its core, the film is controlled by a readymade computer simulation that models the effects of automation on a hypothetical economy. Menick wrote new software to route the simulator’s data to video editing and audio software. Menick’s software uses the data to change both the montage and the score, the latter composed in collaboration with New York-based composer Ben Shirken. The original data remains hidden, the final work is constantly changing, its sound and image never repeating.

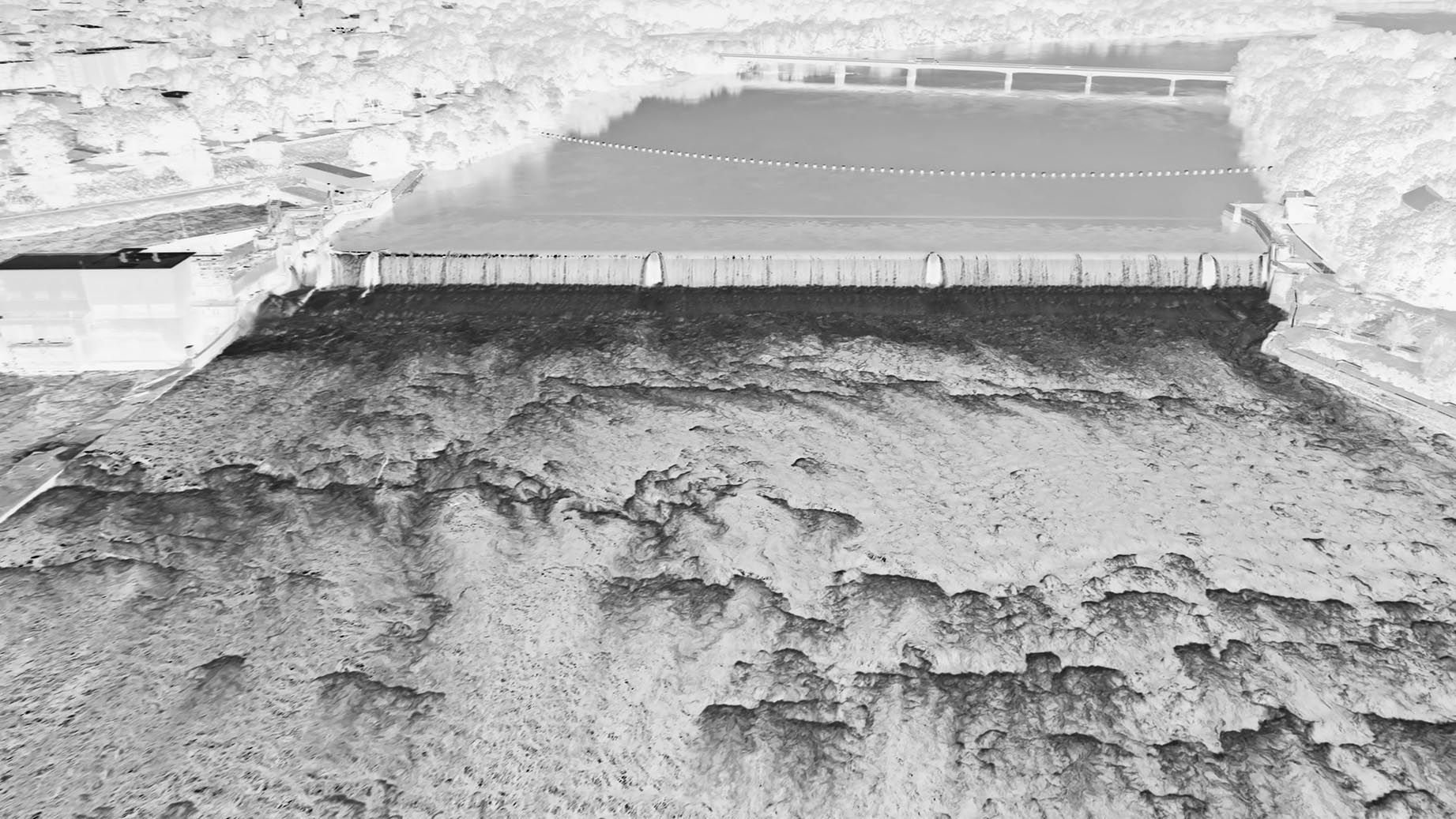

The project began with an invitation from artist Anthony Discenza to develop a work at Lower Cavity, the exhibition space and residency he runs in Holyoke, Massachusetts. After some research, Menick discovered that Holyoke was the site where the first public version of the Telharmonium was built. In the early 1900s, when Cahill worked there, Holyoke was a wealthy industrially advanced city. The city itself is a kind of machine made up of a system of enormous mills powered by canals and the nearby Connecticut River. At one time, Holyoke enjoyed an almost near-monopoly on American paper production. Today, Holyoke is an example of post-industrial decline: it is one of the poorest cities in the state, with roughly 30 percent of the population living below the poverty line.

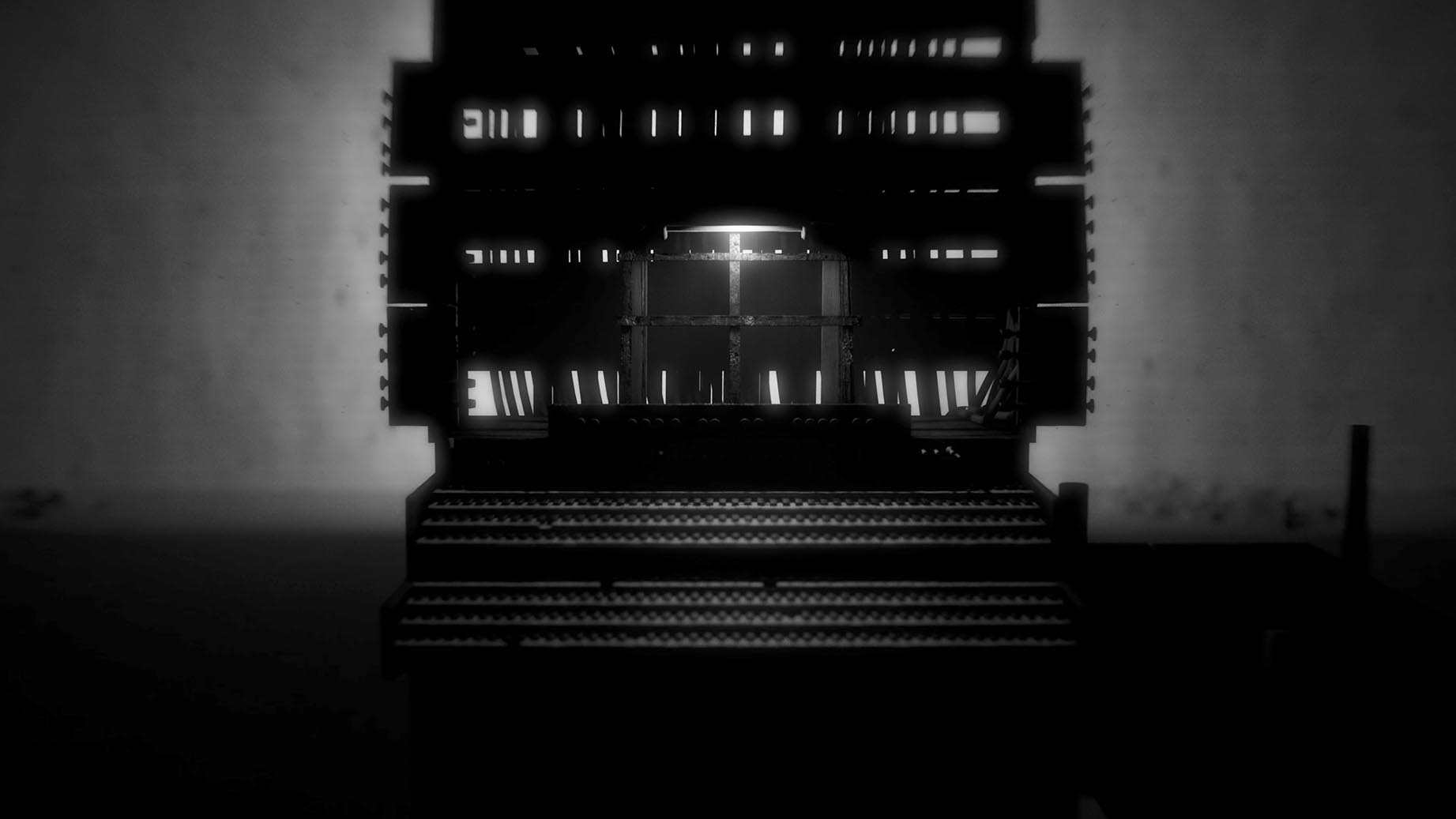

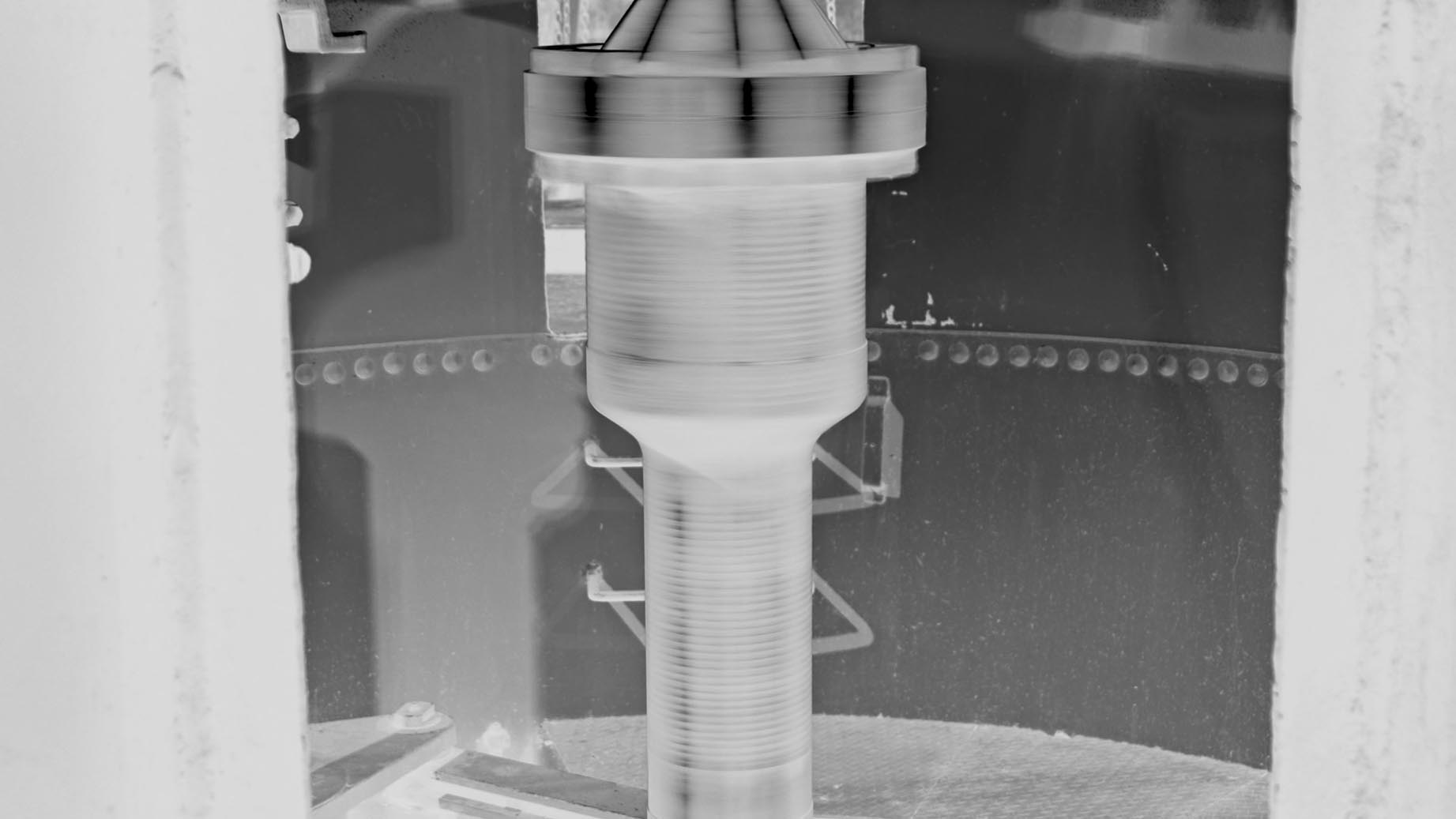

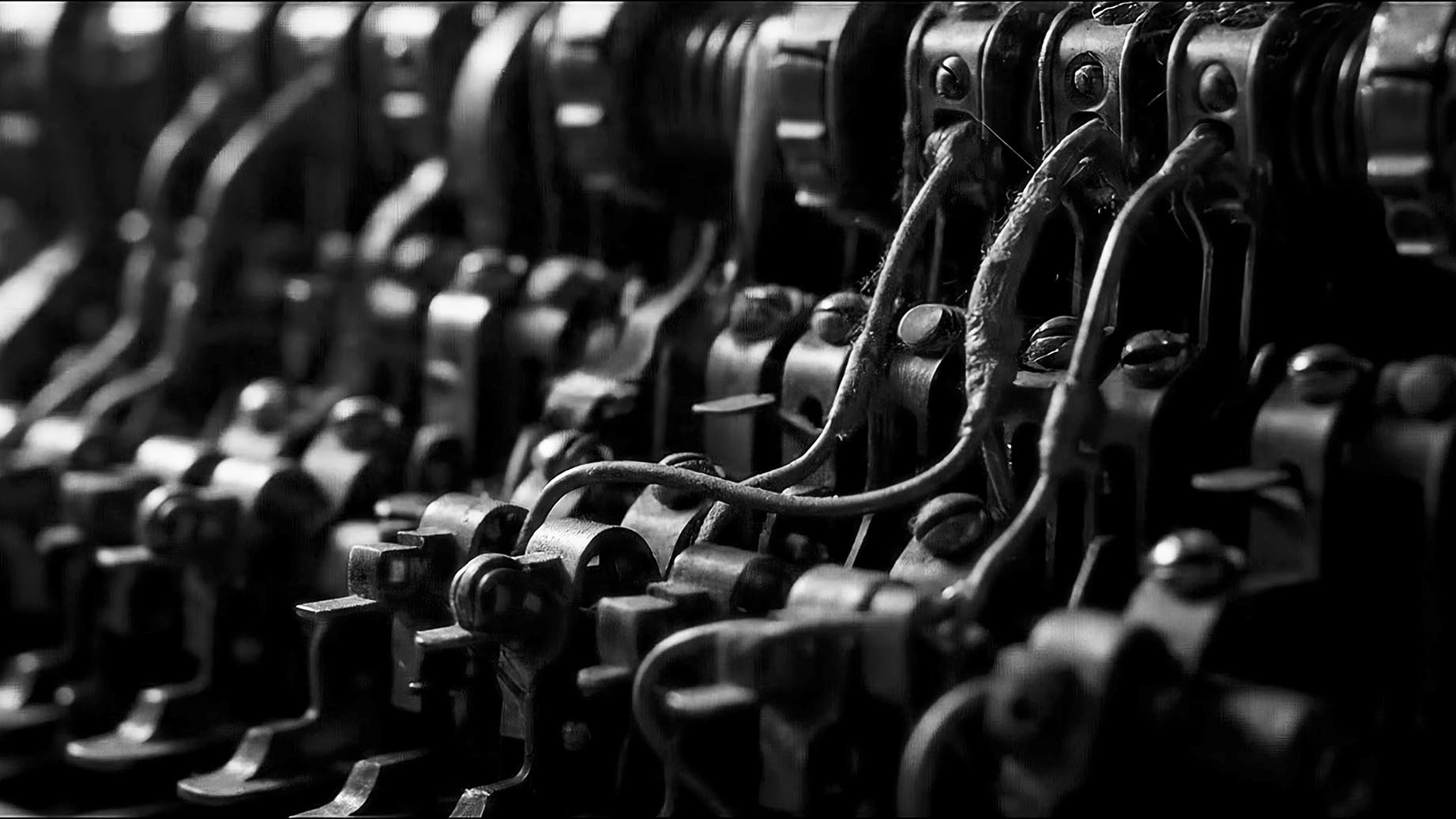

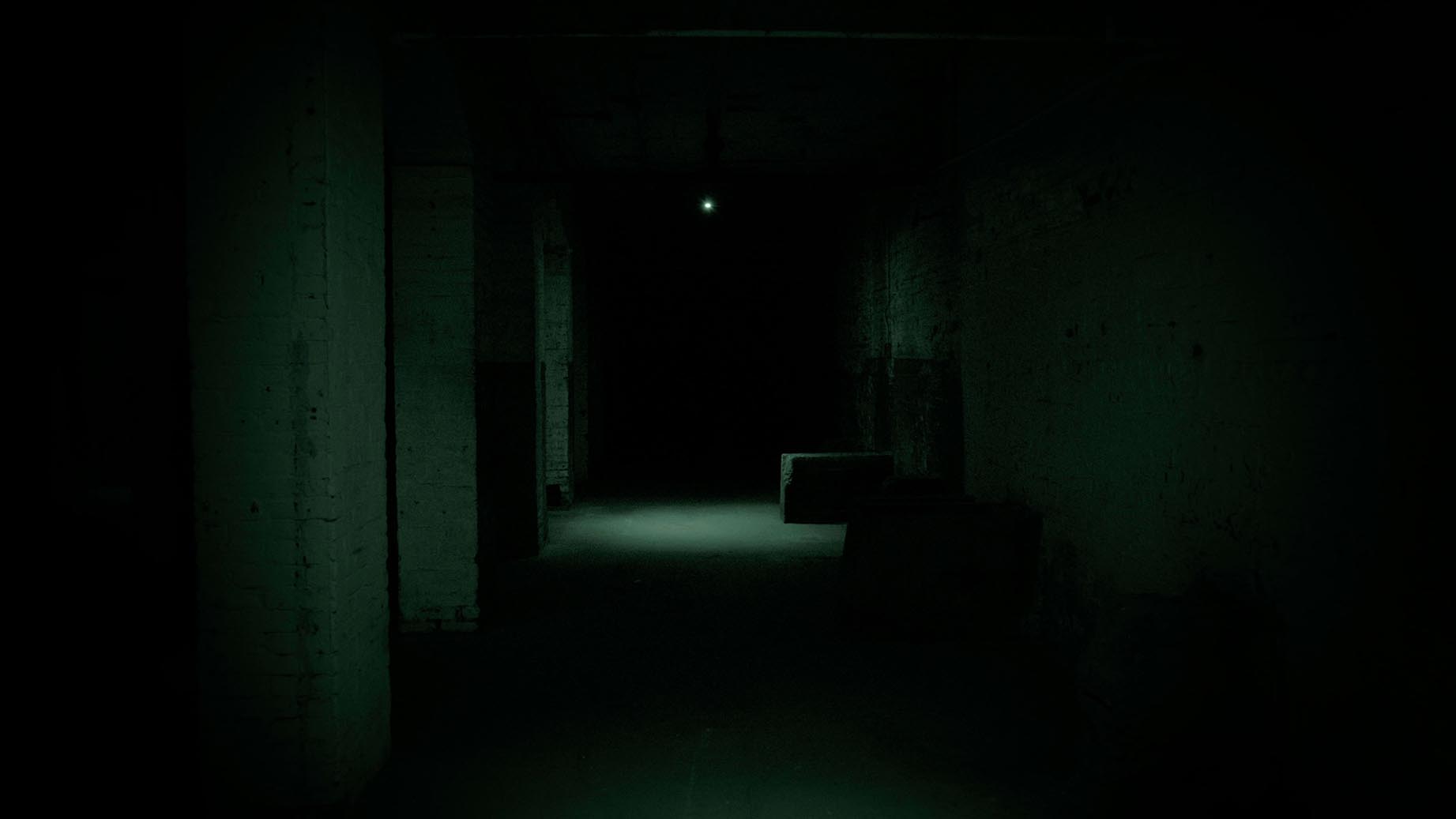

The footage of Holyoke was shot with thermal, infrared, drone, and night vision cameras, suggesting a machinic gaze over the city. These images are paired with computer renderings of speculative reconstructions of the Telharmonium, drawn from the few surviving photographs, and AI-generated depictions of telephone switch systems. The resulting montage, more machinic than cinematic, is assembled by Menick’s software from hundreds of shots. Over these images, a custom-made synthetic voice speaks in fragments about the Telharmonium, telephony, telepathy, and related topics. The voice is complemented by Shirken’s generative score, likewise machinic in its composition. Its composition suggests industrial sound design more than a film score, having been composed from some of the same additive synthesis principles as the original Telharmonium.

The Telharmonium failed as a business. Investors could not recoup their costs, and poorly insulated phone lines leaked its sounds into ordinary phone calls. (The US Navy even complained of symphonies interrupting their conversations.) The enterprise collapsed within a few years, though Cahill continued building new Telharmoniums until his death in 1934. The instrument’s principles lived on in the Hammond organ, which miniaturized the technology and achieved lasting success. Cahill and his device were forgotten, and no recordings of the Telharmonium survive.

The artist would like to thank Matta Gallery, Anthony Discenza, and KADIST for their financial and creative support.