A Million Random Digits

During the early 1950s, John Cage isolated himself in one of Harvard University’s anechoic chambers. He did so to experience “pure silence,” and as the story is often told, his pounding heart and whining nervous system disappointed him. He learned that absolute silence, as a conscious experience, was impossible.

Cage sought pure silence, but was he as strict about his other working method, chance? Randomness is as elusive as silence. A coin toss favors one side over the other, depending on the physics of the toss. It’s not equal odds. Likewise, a personal computer can only produces a relatively random number. If played out over a long enough period, patterns can be detected in most “random” systems.

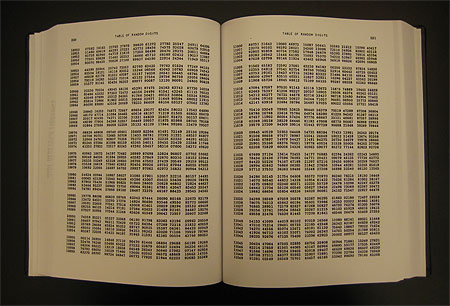

But in 1955, a few years after Cage visited Harvard, a group of researchers at the RAND Corporation published the results of an eight-year inquiry into pure chance. Their researches resulted in the wonderfully titled, A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates. It is a massive reference book comprised of a short technical introduction followed by four hundred pages of random digits and two hundred more of random normal deviates.

Who would use such a beautiful thing? Cryptographers, statisticians, and game designers, but no artist probably did. The book is an artistic project in itself, something done simply for the heady pleasure, not unlike Alighiero Boetti’s Classifying the thousand longest rivers in the world or On Kawara's One Million Years. As quoted in a 2001 New York Times article referenced in the book’s updated introduction, the RAND project is paradoxical, its success based on “how to use order to generate disorder.” Aren’t we again talking about a research similar to that conducted by many postwar artists? Aren’t these mathematicians, researchers and scientists making a procedure that covers its own process, writing a book without an author?